Beyond the Basics¶

In Basics, you learned how to set up BeagleBone Black, and Sensors, Displays and Other Outputs, and Motors showed how to interface to the physical world. The remainder of the book moves into some more exciting advanced topics, and this chapter gets you ready for them.

The recipes in this chapter assume that you are running Linux on your host computer (Selecting an OS for Your Development Host Computer) and are comfortable with using Linux. We continue to assume that you are logged in as debian on your Bone.

Running Your Bone Standalone¶

Problem¶

You want to use BeagleBone Black as a desktop computer with keyboard, mouse, and an HDMI display.

Solution¶

The Bone comes with USB and a microHDMI output. All you need to do is connect your keyboard, mouse, and HDMI display to it.

To make this recipe, you will need:

Standard HDMI cable and female HDMI-to-male microHDMI adapter, or

MicroHDMI-to-HDMI adapter cable

HDMI monitor

USB keyboard and mouse

Powered USB hub

Note

The microHDMI adapter is nice because it allows you to use a regular HDMI cable with the Bone. However, it will block other ports and can damage the Bone if you aren’t careful. The microHDMI-to-HDMI cable won’t have these problems.

Tip

You can also use an HDMI-to-DVI cable and use your Bone with a DVI-D display.

The adapter looks something like Female HDMI-to-male microHDMI adapter.

Fig. 324 Female HDMI-to-male microHDMI adapter¶

Plug the small end into the microHDMI input on the Bone and plug your HDMI cable into the other end of the adapter and your monitor. If nothing displays on your Bone, reboot.

If nothing appears after the reboot, edit the /boot/uEnv.txt file. Search for the line containing

disable_uboot_overlay_video=1 and make sure it’s commented out:

###Disable auto loading of virtual capes (emmc/video/wireless/adc)

#disable_uboot_overlay_emmc=1

#disable_uboot_overlay_video=1

Then reboot.

The /boot/uEnv.txt file contains a number of configuration commands that are executed at boot time.

The # character is used to add comments; that is, everything to the right of a +# is ignored by the

Bone and is assumed to be for humans to read. In the previous example, ###Disable auto loading is

a comment that informs us the next line(s) are for disabling things. Two disable_uboot_overlay

commands follow. Both should be commented-out and won’t be executed by the Bone.

Why not just remove the line? Later, you might decide you need more general-purpose input/output

(GPIO) pins and don’t need the HDMI display. If so, just remove the # from the disable_uboot_overlay_video=1

command. If you had completely removed the line earlier, you would have to look up the details somewhere to re-create it.

When in doubt, comment-out don’t delete.

Note

If you want to re-enable the HDMI audio, just comment-out the line you added.

The Bone has only one USB port, so you will need to get either a keyboard with a USB hub or a USB hub. Plug the USB hub into the Bone and then plug your keyboard and mouse in to the hub. You now have a Beagle workstation no host computer is needed.

Tip

A powered hub is recommended because USB can supply only 500 mA, and you’ll want to plug many things into the Bone.

This recipe disables the HDMI audio, which allows the Bone to try other resolutions. If this fails, see BeagleBoneBlack HDMI for how to force the Bone’s resolution to match your monitor.

Selecting an OS for Your Development Host Computer¶

Problem¶

Your project needs a host computer, and you need to select an operating system (OS) for it.

Solution¶

For projects that require a host computer, we assume that you are running Linux Ubuntu 22.04 LTS. You can be running either a native installation, through Windows Subsystem for Linux, via a virtual machine such as VirtualBox, or in the cloud (Microsoft Azure or Amazon Elastic Compute Cloud, EC2, for example).

Recently I’ve been preferring Windows Subsystem for Linux.

Getting to the Command Shell via SSH¶

Problem¶

You want to connect to the command shell of a remote Bone from your host computer.

Solution¶

Running Python and JavaScript Applications from Visual Studio Code shows how to run shell commands in the Visual Studio Code bash tab. However, the Bone has Secure Shell (SSH) enabled right out of the box, so you can easily connect by using the following command to log in as user debian, (note the $ at the end of the prompt):

host$ ssh debian@192.168.7.2

Warning: Permanently added '192.168.7.2' (ED25519) to the list of known hosts.

Debian GNU/Linux 11

BeagleBoard.org Debian Bullseye IoT Image 2023-06-03

Support: https://bbb.io/debian

default username:password is [debian:temppwd]

The programs included with the Debian GNU/Linux system are free software;

the exact distribution terms for each program are described in the

individual files in /usr/share/doc/*/copyright.

Debian GNU/Linux comes with ABSOLUTELY NO WARRANTY, to the extent

permitted by applicable law.

Last login: Thu Jun 8 14:02:40 2023 from 192.168.7.1

bone$

Default password¶

debian has the default password temppwd. It’s best to change the password:

bone$ password

Changing password for debian.

(current) UNIX password:

Enter new UNIX password:

Retype new UNIX password:

password: password updated successfully

Removing the Message of the Day¶

Problem¶

Every time you login a long message is displayed that you don’t need to see.

Solution¶

The contents of the files /etc/motd, /etc/issue and /etc/issue.net are displayed everytime you long it. You can prevent them from being displayed by moving them elsewhere.

bone$ sudo mv /etc/motd /etc/motd.orig

bone$ sudo mv /etc/issue /etc/issue.orig

bone$ sudo mv /etc/issue.net /etc/issue.net.orig

Now, the next time you ssh in they won’t be displayed.

Getting to the Command Shell via the Virtual Serial Port¶

Problem¶

You want to connect to the command shell of a remote Bone from your host computer without using SSH.

Solution¶

Sometimes, you can’t connect to the Bone via SSH, but you have a network working over USB to the Bone. There is a way to access the command line to fix things without requiring extra hardware. (Viewing and Debugging the Kernel and u-boot Messages at Boot Time shows a way that works even if you don’t have a network working over USB, but it requires a special serial-to-USB cable.)

Note

This method doesn’t work with WSL.

First, check to ensure that the serial port is there. On the host computer, run the following command:

host$ ls -ls /dev/ttyACM0

0 crw-rw---- 1 root dialout 166, 0 Jun 19 11:47 /dev/ttyACM0

/dev/ttyACM0 is a serial port on your host computer that the Bone creates when it boots up. The letters crw-rw—- show that you can’t access it as a normal user. However, you can access it if you are part of dialout group. See if you are in the dialout group:

host$ groups

yoder adm tty uucp dialout cdrom sudo dip plugdev lpadmin sambashare

Looks like I’m already in the group, but if you aren’t, just add yourself to the group:

host$ sudo adduser $USER dialout

You have to run adduser only once. Your host computer will remember the next time you boot up. Now, install and run the screen command:

host$ sudo apt install screen

host$ screen /dev/ttyACM0 115200

Debian GNU/Linux 7 beaglebone ttyGS0

default username:password is [debian:temppwd]

Support/FAQ: http://elinux.org/Beagleboard:BeagleBoneBlack_Debian

The IP Address for usb0 is: 192.168.7.2

beaglebone login:

The /dev/ttyACM0 parameter specifies which serial port to connect to, and 115200

tells the speed of the connection. In this case, it’s 115,200 bits per second.

Viewing and Debugging the Kernel and u-boot Messages at Boot Time¶

Problem¶

You want to see the messages that are logged by BeagleBone Black as it comes to life.

Solution¶

There is no network in place when the Bone first boots up, so Getting to the Command Shell via SSH and Getting to the Command Shell via the Virtual Serial Port won’t work. This recipe uses some extra hardware (FTDI cable) to attach to the Bone’s console serial port.

To make this recipe, you will need:

3.3 V FTDI cable

Warning

Be sure to get a 3.3 V FTDI cable (shown in FTDI cable), because the 5 V cables won’t work.

Tip

The Bone’s Serial Debug J1 connector has Pin 1 connected to ground, Pin 4 to receive, and Pin 5 to transmit. The other pins are not attached.

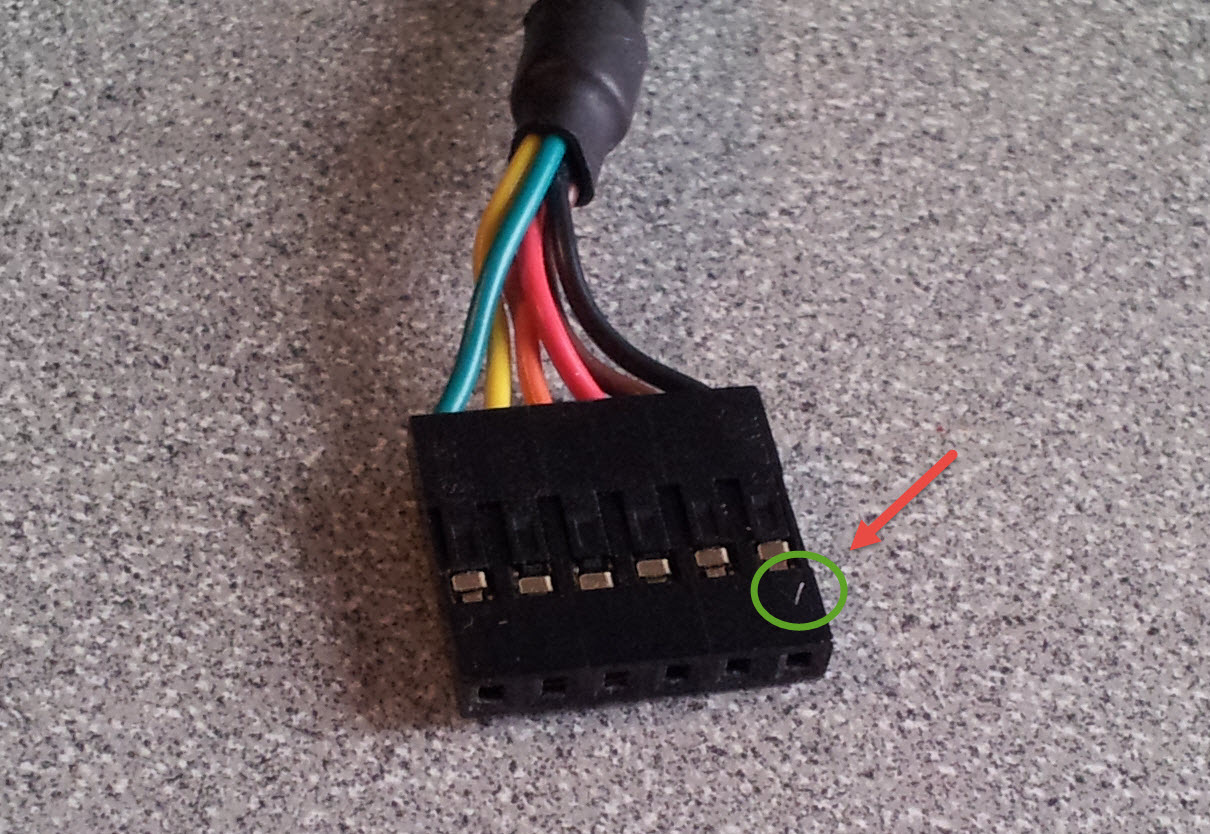

Fig. 325 FTDI cable¶

Look for a small triangle at the end of the FTDI cable (FTDI connector). It’s often connected to the black wire.

Fig. 326 FTDI connector¶

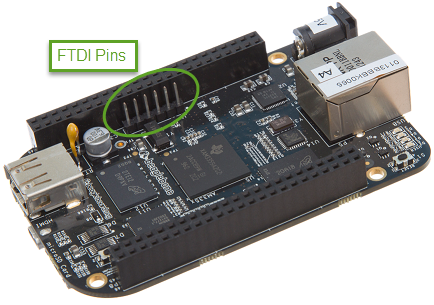

Next, look for the FTDI pins of the Bone (labeled J1 on the Bone), shown in FTDI pins for the FTDI connector. They are next to the P9 header and begin near pin 20. There is a white dot near P9_20.

Fig. 327 FTDI pins for the FTDI connector¶

Plug the FTDI connector into the FTDI pins, being sure to connect

the triangle pin on the connector to the white dot pin of the FTDI connector.

Now, run the following commands on your host computer:

host$ ls -ls /dev/ttyUSB0

0 crw-rw---- 1 root dialout 188, 0 Jun 19 12:43 /dev/ttyUSB0

host$ sudo adduser $USER dialout

host$ screen /dev/ttyUSB0 115200

Debian GNU/Linux 7 beaglebone ttyO0

default username:password is [debian:temppwd]

Support/FAQ: http://elinux.org/Beagleboard:BeagleBoneBlack_Debian

The IP Address for usb0 is: 192.168.7.2

beaglebone login:

Note

Your screen might initially be blank. Press Enter a couple times to see the login prompt.

Verifying You Have the Latest Version of the OS on Your Bone from the Shell¶

Problem¶

You are logged in to your Bone with a command prompt and want to know what version of the OS you are running.

Solution¶

Log in to your Bone and enter the following command:

bone$ cat /etc/dogtag

BeagleBoard.org Debian Bullseye IoT Image 2023-06-03

Verifying You Have the Latest Version of the OS on Your Bone shows how to open the /etc/dogtag file to see the OS version.

See Running the Latest Version of the OS on Your Bone if you need to update your OS.

Controlling the Bone Remotely with a VNC¶

Problem¶

You want to access the BeagleBone’s graphical desktop from your host computer.

Solution¶

Install and run a Virtual Network Computing (VNC) server:

bone$ sudo apt update

bone$ sudo apt install tightvncserver

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree... Done

Reading state information... Done

The following additional packages will be installed:

...

update-alternatives: using /usr/bin/Xtightvnc to provide /usr/bin/Xvnc (Xvnc) in auto mode

update-alternatives: using /usr/bin/tightvncpasswd to provide /usr/bin/vncpasswd (vncpasswd) in auto mode

Processing triggers for libc-bin (2.31-13+deb11u6) ...

bone$ tightvncserver

You will require a password to access your desktops.

Password:

Verify:

Would you like to enter a view-only password (y/n)? n

xauth: (argv):1: bad display name "beaglebone:1" in "add" command

New 'X' desktop is beaglebone:1

Creating default startup script /home/debian/.vnc/xstartup

Starting applications specified in /home/debian/.vnc/xstartup

Log file is /home/debian/.vnc/beagleboard:1.log

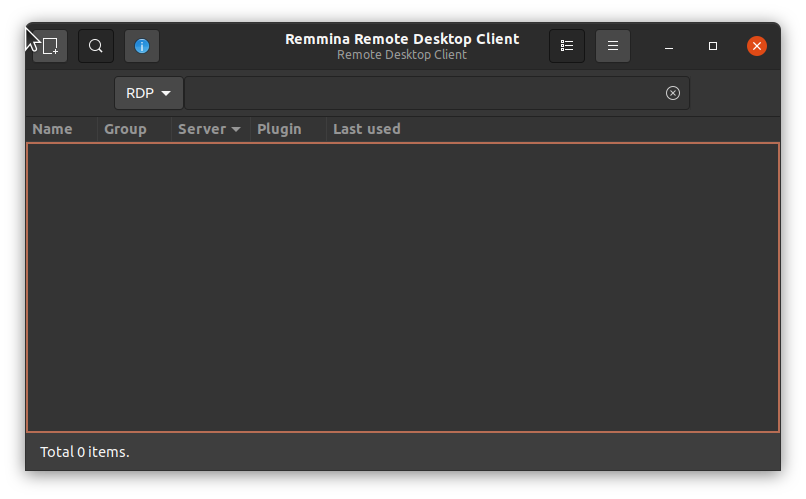

To connect to the Bone, you will need to run a VNC client. There are many to choose from. Remmina Remote Desktop Client is already installed on Ubuntu. Start and select the new remote desktop file button (Creating a new remote desktop file in Remmina Remote Desktop Client).

Fig. 328 Creating a new remote desktop file in Remmina Remote Desktop Client¶

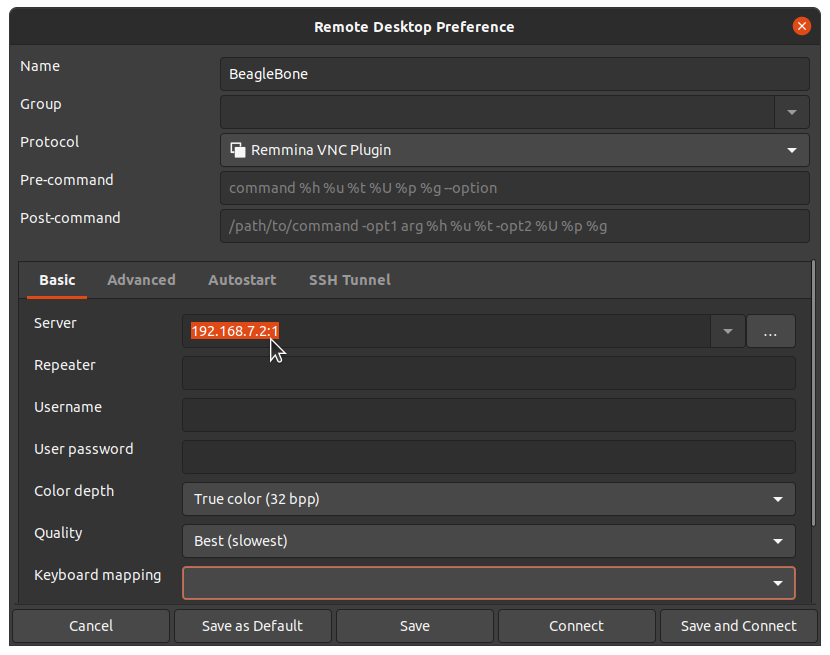

Give your connection a name, being sure to select “Remmina VNC Plugin” Also, be sure to add :1 after the server address, as shown in Configuring the Remmina Remote Desktop Client. This should match the :1 that was displayed when you started vncserver.

Fig. 329 Configuring the Remmina Remote Desktop Client¶

Click Connect to start graphical access to your Bone, as shown in The Remmina Remote Desktop Client showing the BeagleBone desktop.

Fig. 330 The Remmina Remote Desktop Client showing the BeagleBone desktop¶

Tip

You might need to resize the VNC screen on your host to see the bottom menu bar on your Bone.

Note

You need to have X Windows installed and running for the VNC to work. Here’s how to install it. This needs some 250M of disk space and 19 minutes to install.

bone$ bone$ sudo apt install bbb.io-xfce4-desktop

bone$ sdo cp /etc/bbb.io/templates/fbdev.xorg.conf /etc/X11/xorg.conf

bone$ startxfce4

/usr/bin/startxfce4: Starting X server

/usr/bin/startxfce4: 122: exec: xinit: not found

Learning Typical GNU/Linux Commands¶

Problem¶

There are many powerful commands to use in Linux. How do you learn about them?

Solution¶

Common Linux commands lists many common Linux commands.

Command |

Action |

pwd |

show current directory |

cd |

change current directory |

ls |

list directory contents |

chmod |

change file permissions |

chown |

change file ownership |

cp |

copy files |

mv |

move files |

rm |

remove files |

mkdir |

make directory |

rmdir |

remove directory |

cat |

dump file contents |

less |

progressively dump file |

vi |

edit file (complex) |

nano |

edit file (simple) |

head |

trim dump to top |

tail |

trim dump to bottom |

echo |

print/dump value |

env |

dump environment variables |

export |

set environment variable |

history |

dump command history |

grep |

search dump for strings |

man |

get help on command |

apropos |

show list of man pages |

find |

search for files |

tar |

create/extract file archives |

gzip |

compress a file |

gunzip |

decompress a file |

du |

show disk usage |

df |

show disk free space |

mount |

mount disks |

tee |

write dump to file in parallel |

hexdump |

readable binary dumps |

whereis |

locates binary and source files |

Editing a Text File from the GNU/Linux Command Shell¶

Problem¶

You want to run an editor to change a file.

Solution¶

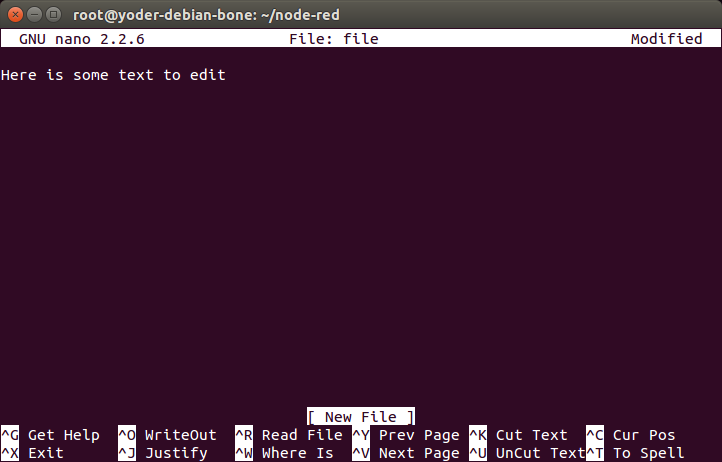

The Bone comes with a number of editors. The simplest to learn is nano. Just enter the following command:

bone$ nano file

You are now in nano (Editing a file with nano). You can’t move around the screen using the mouse, so use the arrow keys. The bottom two lines of the screen list some useful commands. Pressing ^G (Ctrl-G) will display more useful commands. ^X (Ctrl-X) exits nano and gives you the option of saving the file.

Fig. 331 Editing a file with nano¶

Tip

By default, the file you create will be saved in the directory from which you opened nano.

Many other text editors will run on the Bone. vi, vim, emacs, and even eclipse are all supported. See Installing Additional Packages from the Debian Package Feed to learn if your favorite is one of them.

Establishing an Ethernet-Based Internet Connection¶

Problem¶

You want to connect your Bone to the Internet using the wired network connection.

Solution¶

Plug one end of an Ethernet patch cable into the RJ45 connector on the Bone (see The RJ45 port on the Bone) and the other end into your home hub/router. The yellow and green link lights on both ends should begin to flash.

Fig. 332 The RJ45 port on the Bone¶

If your router is already configured to run DHCP (Dynamical Host Configuration Protocol), it will automatically assign an IP address to the Bone.

Warning

It might take a minute or two for your router to detect the Bone and assign the IP address.

To find the IP address, open a terminal window and run the ip command:

bone$ ip a

1: lo: <LOOPBACK,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 65536 qdisc noqueue state UNKNOWN group default qlen 1000

link/loopback 00:00:00:00:00:00 brd 00:00:00:00:00:00

inet 127.0.0.1/8 scope host lo

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 ::1/128 scope host

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

2: eth0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc mq state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether c8:a0:30:a6:26:e8 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.0.5.144/24 brd 10.0.5.255 scope global dynamic eth0

valid_lft 80818sec preferred_lft 80818sec

inet6 fe80::caa0:30ff:fea6:26e8/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

3: usb0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether c2:3f:44:bb:41:0f brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.7.2/24 brd 192.168.7.255 scope global usb0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::c03f:44ff:febb:410f/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

4: usb1: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 76:7e:49:46:1b:78 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.6.2/24 brd 192.168.6.255 scope global usb1

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::747e:49ff:fe46:1b78/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

5: can0: <NOARP,ECHO> mtu 16 qdisc no-op state DOWN group default qlen 10

link/can

6: can1: <NOARP,ECHO> mtu 16 qdisc no-op state DOWN group default qlen 10

link/can

My Bone is connected to the Internet in two ways: via the RJ45 connection (eth0) and via the USB cable (usb0). The inet field shows that my Internet address is 10.0.5.144 for the RJ45 connector.

On my university campus, you must register your MAC address before any device will work on the network. The HWaddr field gives the MAC address. For eth0, it’s c8:a0:30:a6:26:e8.

The IP address of your Bone can change. If it’s been assigned by DHCP, it can change at any time. The MAC address, however, never changes; it is assigned to your ethernet device when it’s manufactured.

Warning

When a Bone is connected to some networks it becomes visible to the world. If you don’t secure your Bone,

the world will soon find it. See Default password and Setting Up a Firewall

On many home networks, you will be behind a firewall and won’t be as visible.

Establishing a WiFi-Based Internet Connection¶

Problem¶

You want BeagleBone Black to talk to the Internet using a USB wireless adapter.

Solution¶

Tip

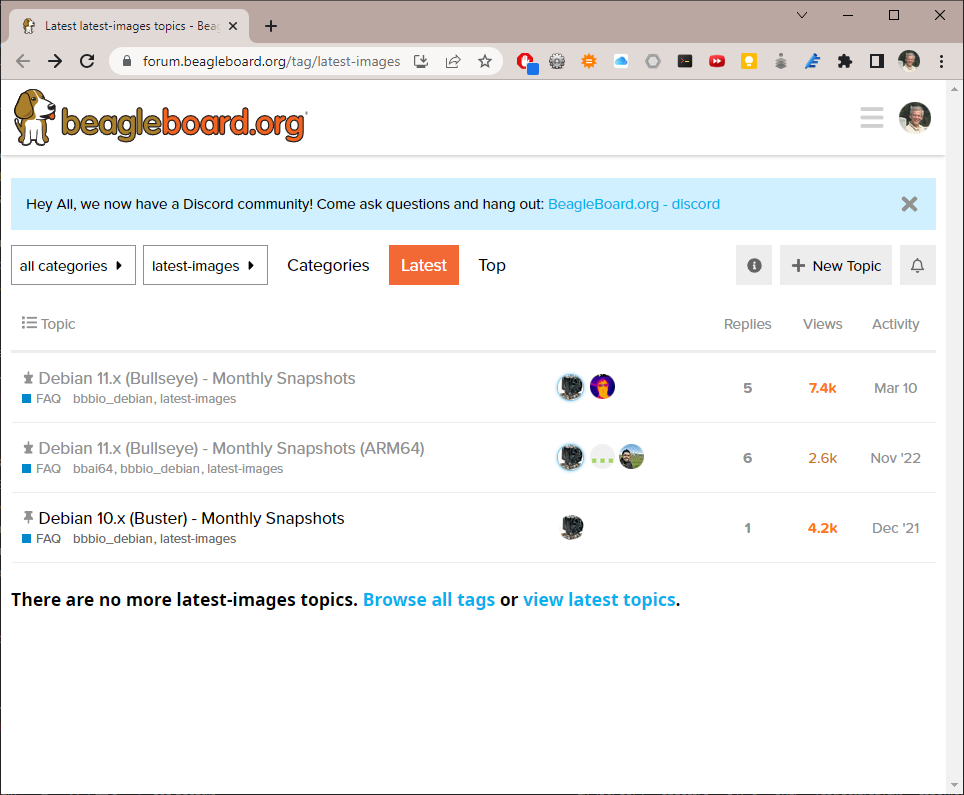

For the correct instructions for the image you are using, go to latest-images and click on the image you are using.

I’m running Debian 11.x (Bullseye), the top one, on the BeagleBone Black.

Fig. 333 Latest Beagle Images¶

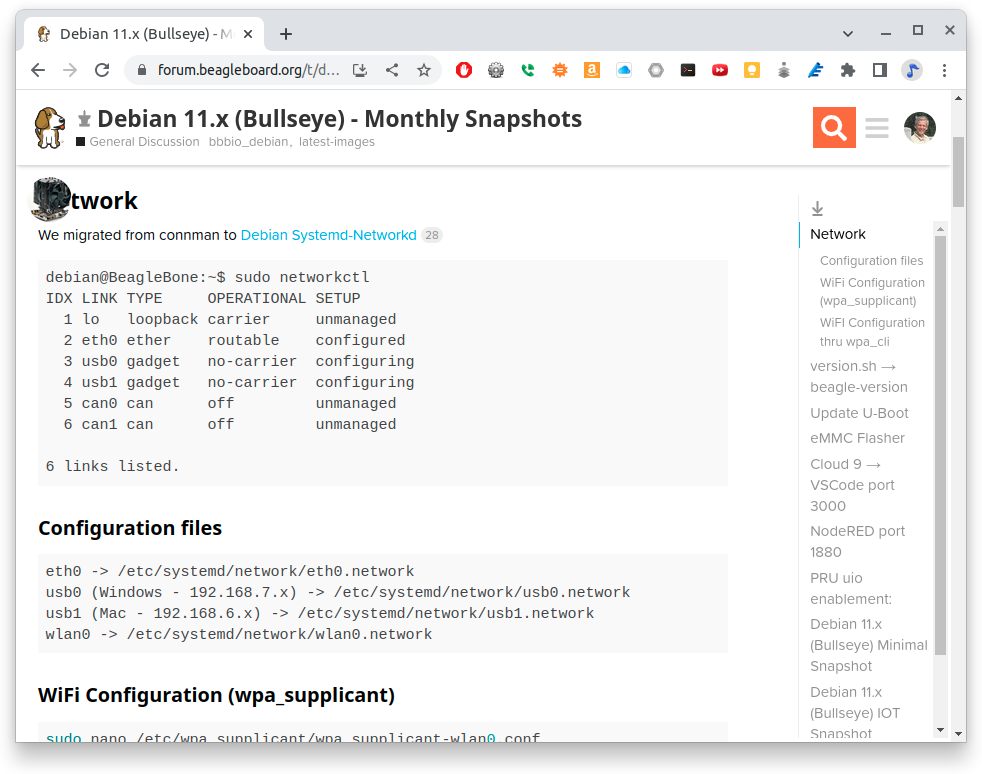

Scroll to the top of the page and you’ll see instructions on setting up Wifi. The instructions here are based on using networkctl.

Fig. 334 Instructions for setting up your network.¶

Several WiFi adapters work with the Bone. Check WiFi Adapters for the latest list.

To make this recipe, you will need:

USB Wifi adapter

5 V external power supply

Warning

Most adapters need at least 1 A of current to run, and USB supplies only 0.5 A, so be sure to use an external power supply. Otherwise, you will experience erratic behavior and random crashes.

First, plug in the WiFi adapter and the 5 V external power supply and reboot.

Then run lsusb to ensure that your Bone found the adapter:

bone$ lsusb

Bus 001 Device 002: ID 0bda:8176 Realtek Semiconductor Corp. RTL8188CUS 802.11n

WLAN Adapter

Bus 001 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Bus 002 Device 001: ID 1d6b:0002 Linux Foundation 2.0 root hub

Note

There is a well-known bug in the Bone’s 3.8 kernel series that prevents USB devices from being discovered when hot-plugged, which is why you should reboot. Newer kernels should address this issue.

Next, run networkctl to find your adapter’s name. Mine is called wlan0, but you might see other names, such as ra0.

bone$ networkctl

IDX LINK TYPE OPERATIONAL SETUP

1 lo loopback carrier unmanaged

2 eth0 ether no-carrier configuring

3 usb0 gadget routable configured

4 usb1 gadget routable configured

5 can0 can off unmanaged

6 can1 can off unmanaged

7 wlan0 wlan routable configured

8 SoftAp0 wlan routable configured

8 links listed.

If no name appears, try ip a:

bone$ ip a

...

2: eth0: <NO-CARRIER,BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state DOWN group default qlen 1000

link/ether c8:a0:30:a6:26:e8 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

3: usb0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc pfifo_fast state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether c2:3f:44:bb:41:0f brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 192.168.7.2/24 brd 192.168.7.255 scope global usb0

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

inet6 fe80::c03f:44ff:febb:410f/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

...

7: wlan0: <BROADCAST,MULTICAST,UP,LOWER_UP> mtu 1500 qdisc mq state UP group default qlen 1000

link/ether 64:69:4e:7e:5c:e4 brd ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff

inet 10.0.7.21/24 brd 10.0.7.255 scope global dynamic wlan0

valid_lft 85166sec preferred_lft 85166sec

inet6 fe80::6669:4eff:fe7e:5ce4/64 scope link

valid_lft forever preferred_lft forever

Next edit the configuration file */etc/wpa_supplicant/wpa_supplicant-wlan0.conf*.

bone$ sudo nano /etc/wpa_supplicant/wpa_supplicant-wlan0.conf

In the file you’ll see:

ctrl_interface=DIR=/run/wpa_supplicant GROUP=netdev

update_config=1

#country=US

network={

ssid="Your SSID"

psk="Your Password"

}

Change the ssid and psk entries for your network. Save your file, then run:

bone$ sudo systemctl restart systemd-networkd

bone$ ip a

bone$ ping -c2 google.com

PING google.com (142.250.191.206) 56(84) bytes of data.

64 bytes from ord38s31-in-f14.1e100.net (142.250.191.206): icmp_seq=1 ttl=115 time=19.5 ms

64 bytes from ord38s31-in-f14.1e100.net (142.250.191.206): icmp_seq=2 ttl=115 time=19.4 ms

--- google.com ping statistics ---

2 packets transmitted, 2 received, 0% packet loss, time 1001ms

rtt min/avg/max/mdev = 19.387/19.450/19.513/0.063 ms

wlan0 should now have an ip address and you should be on the network. If not, try rebooting.

Setting Up a Firewall¶

Problem¶

You have put your Bone on the network and want to limit which IP addresses can access it.

Solution¶

How-To Geek has a great posting on how do use ufw, the “uncomplicated firewall”. Check out How to Secure Your Linux Server with a UFW Firewall. I’ll summarize the initial setup here.

First install and check the status:

bone$ sudo apt update

bone$ sudo apt install ufw

bone$ sudo ufw status

Status: inactive

Now turn off everything coming in and leave on all outgoing. Note, this won’t take effect until ufw is enabled.

bone$ sudo ufw default deny incoming

bone$ sudo ufw default allow outgoing

Don’t enable yet, make sure ssh still has access

bone$ sudo ufw allow 22

Just to be sure, you can install nmap on your host computer to see what ports are currently open.

host$ sudo apt update

host$ sudo apt install nmap

host$ nmap 192.168.7.2

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2022-07-09 13:37 EDT

Nmap scan report for bone (192.168.7.2)

Host is up (0.014s latency).

Not shown: 997 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

3000/tcp open ppp

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0.19 seconds

Currently there are three ports visible: 22, 80 and 3000 (visual studio code). Now turn on the firewall and see what happens.

bone$ sudo ufw enable

Command may disrupt existing ssh connections. Proceed with operation (y|n)? y

Firewall is active and enabled on system startup

host$ nmap 192.168.7.2

Starting Nmap 7.80 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2022-07-09 13:37 EDT

Nmap scan report for bone (192.168.7.2)

Host is up (0.014s latency).

Not shown: 999 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 0.19 seconds

Only port 22 (ssh) is accessible now.

The firewall will remain on, even after a reboot. Disable it now if you don’t want it on.

bone$ sudo ufw disable

Firewall stopped and disabled on system startup

See the How-To Geek article for more examples.

Installing Additional Packages from the Debian Package Feed¶

Problem¶

You want to do more cool things with your BeagleBone by installing more programs.

Solution¶

Warning

Your Bone needs to be on the network for this to work. See Establishing an Ethernet-Based Internet Connection, Establishing a WiFi-Based Internet Connection, or Sharing the Host’s Internet Connection over USB.

The easiest way to install more software is to use apt:

bone$ sudo apt update

bone$ sudo apt install "name of software"

A sudo is necessary since you aren’t running as root. The first command downloads package lists from various repositories and updates them to get information on the newest versions of packages and their dependencies. (You need to run it only once a week or so.) The second command fetches the software and installs it and all packages it depends on.

How do you find out what software you can install? Try running this:

bone$ apt-cache pkgnames | sort > /tmp/list

bone$ wc /tmp/list

67974 67974 1369852 /tmp/list

bone$ less /tmp/list

The first command lists all the packages that apt knows about and sorts them and stores

them in /tmp/list. The second command shows why you want to put the list in a file.

The wc command counts the number of lines, words, and characters in a file. In our case,

there are over 67,000 packages from which we can choose! The less command displays the sorted

list, one page at a time. Press the space bar to go to the next page. Press q to quit.

Suppose that you would like to install an online dictionary (dict). Just run the following command:

bone$ sudo apt install dict

Now you can run dict.

Removing Packages Installed with apt¶

Problem¶

You’ve been playing around and installing all sorts of things with apt and now you want to clean things up a bit.

Solution¶

apt has a remove option, so you can run the following command:

bone$ sudo apt remove dict

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree

Reading state information... Done

The following packages were automatically installed and are no longer required:

libmaa3 librecode0 recode

Use 'apt autoremove' to remove them.

The following packages will be REMOVED:

dict

0 upgraded, 0 newly installed, 1 to remove and 27 not upgraded.

After this operation, 164 kB disk space will be freed.

Do you want to continue [Y/n]? y

Copying Files Between the Onboard Flash and the MicroSD Card¶

Problem¶

You want to move files between the onboard flash and the microSD card.

Solution¶

If you booted from the microSD card, run the following command:

bone$ df -h

Filesystem Size Used Avail Use% Mounted on

rootfs 7.2G 2.0G 4.9G 29% /

udev 10M 0 10M 0% /dev

tmpfs 100M 1.9M 98M 2% /run

/dev/mmcblk0p2 7.2G 2.0G 4.9G 29% /

tmpfs 249M 0 249M 0% /dev/shm

tmpfs 249M 0 249M 0% /sys/fs/cgroup

tmpfs 5.0M 0 5.0M 0% /run/lock

tmpfs 100M 0 100M 0% /run/user

bone$ ls /dev/mmcblk*

/dev/mmcblk0 /dev/mmcblk0p2 /dev/mmcblk1boot0 /dev/mmcblk1p1

/dev/mmcblk0p1 /dev/mmcblk1 /dev/mmcblk1boot1

The df command shows what partitions are already mounted.

The line /dev/mmcblk0p2 7.2G 2.0G 4.9G 29% / shows that mmcblk0 partition p2

is mounted as /, the root file system. The general rule is that the media you’re booted from

(either the onboard flash or the microSD card) will appear as mmcblk0.

The second partition (p2) is the root of the file system.

The ls command shows what devices are available to mount. Because mmcblk0 is already mounted, /dev/mmcblk1p1 must be the other media that we need to mount. Run the following commands to mount it:

bone$ cd /mnt

bone$ sudo mkdir onboard

bone$ ls onboard

bone$ sudo mount /dev/mmcblk1p1 onboard/

bone$ ls onboard

bin etc lib mnt proc sbin sys var

boot home lost+found nfs-uEnv.txt root selinux tmp

dev ID.txt media opt run srv usr

The cd command takes us to a place in the file system where files are commonly mounted.

The mkdir command creates a new directory (onboard) to be a mount point. The ls

command shows there is nothing in onboard. The mount command makes the contents of

the onboard flash accessible. The next ls shows there now are files in onboard.

These are the contents of the onboard flash, which can be copied to and from like any other file.

This same process should also work if you have booted from the onboard flash. When you are done with the onboard flash, you can unmount it by using this command:

bone$ sudo umount /mnt/onboard

Freeing Space on the Onboard Flash or MicroSD Card¶

Problem¶

You are starting to run out of room on your microSD card (or onboard flash) and have removed several packages you had previously installed (Removing Packages Installed with apt), but you still need to free up more space.

Solution¶

To free up space, you can remove preinstalled packages or discover big files to remove.

Removing preinstalled packages¶

You might not need a few things that come preinstalled in the Debian image, including such things as OpenCV, the Chromium web browser, and some documentation.

Note

The Chromium web browser is the open source version of Google’s Chrome web browser. Unless you are using the Bone as a desktop computer, you can probably remove it.

Here’s how you can remove these:

bone$ sudo apt remove bb-node-red-installer (171M)

bone$ sudo apt autoremove

bone$ sudo -rf /usr/share/doc (116M)

bone$ sudo -rf /usr/share/man (19M)

Discovering big files¶

The du (disk usage) command offers a quick way to discover big files:

bone$ sudo du -shx /*

12M /bin

160M /boot

0 /dev

23M /etc

835M /home

4.0K /ID.txt

591M /lib

16K /lost+found

4.0K /media

8.0K /mnt

664M /opt

du: cannot access '/proc/1454/task/1454/fd/4': No such file or directory

du: cannot access '/proc/1454/task/1454/fdinfo/4': No such file or directory

du: cannot access '/proc/1454/fd/3': No such file or directory

du: cannot access '/proc/1454/fdinfo/3': No such file or directory

0 /proc

1.4M /root

1.4M /run

13M /sbin

4.0K /srv

0 /sys

48K /tmp

1.6G /usr

1.9G /var

If you booted from the microSD card, du lists the usage of the microSD. If you booted from the onboard flash, it lists the onboard flash usage.

The -s option summarizes the results rather than displaying every file. -h prints it in _human_ form–that is, using M and K postfixes rather than showing lots of digits. The /* specifies to run it on everything in the top-level directory. It looks like a couple of things disappeared while the command was running and thus produced some error messages.

Tip

For more help, try du –help.

The /var directory appears to be the biggest user of space at 1.9 GB. You can then run the

following command to see what’s taking up the space in /var:

bone$ sudo du -sh /var/*

4.0K /var/backups

76M /var/cache

93M /var/lib

4.0K /var/local

0 /var/lock

751M /var/log

4.0K /var/mail

4.0K /var/opt

0 /var/run

16K /var/spool

987M /var/swap

28K /var/tmp

16K /var/www

A more interactive way to explore your disk usage is by installing ncdu (ncurses disk usage):

bone$ sudo apt install ncdu

bone$ ncdu /

After a moment, you’ll see the following:

ncdu 1.15.1 ~ Use the arrow keys to navigate, press ? for help

--- / ------------------------------------------------------------------

. 1.9 GiB [##########] /var

1.5 GiB [######## ] /usr

835.0 MiB [#### ] /home

663.5 MiB [### ] /opt

590.9 MiB [### ] /lib

159.0 MiB [ ] /boot

. 22.8 MiB [ ] /etc

12.5 MiB [ ] /sbin

11.1 MiB [ ] /bin

. 1.4 MiB [ ] /run

. 40.0 KiB [ ] /tmp

! 16.0 KiB [ ] /lost+found

8.0 KiB [ ] /mnt

e 4.0 KiB [ ] /srv

! 4.0 KiB [ ] /root

e 4.0 KiB [ ] /media

4.0 KiB [ ] ID.txt

. 0.0 B [ ] /sys

. 0.0 B [ ] /proc

0.0 B [ ] /dev

Total disk usage: 5.6 GiB Apparent size: 5.5 GiB Items: 206148

ncdu is a character-based graphics interface to du. You can now use your arrow keys to navigate the file structure to discover where the big unused files are. Press ? for help.

Warning

Be careful not to press the d key, because it’s used to delete a file or directory.

Using C to Interact with the Physical World¶

Problem¶

You want to use C on the Bone to talk to the world.

Solution¶

The C solution isn’t as simple as the JavaScript or Python solution, but it does work and is much faster. The approach is the same, write to the /sys/class/gpio files.

1////////////////////////////////////////

2// blinkLED.c

3// Blinks the P9_14 pin

4// Wiring:

5// Setup:

6// See:

7////////////////////////////////////////

8#include <stdio.h>

9#include <string.h>

10#include <unistd.h>

11#define MAXSTR 100

12// Look up P9.14 using gpioinfo | grep -e chip -e P9.14. chip 1, line 18 maps to 50

13int main() {

14 FILE *fp;

15 char pin[] = "50";

16 char GPIOPATH[] = "/sys/class/gpio";

17 char path[MAXSTR] = "";

18

19 // Make sure pin is exported

20 snprintf(path, MAXSTR, "%s%s%s", GPIOPATH, "/gpio", pin);

21 if (!access(path, F_OK) == 0) {

22 snprintf(path, MAXSTR, "%s%s", GPIOPATH, "/export");

23 fp = fopen(path, "w");

24 fprintf(fp, "%s", pin);

25 fclose(fp);

26 }

27

28 // Make it an output pin

29 snprintf(path, MAXSTR, "%s%s%s%s", GPIOPATH, "/gpio", pin, "/direction");

30 fp = fopen(path, "w");

31 fprintf(fp, "out");

32 fclose(fp);

33

34 // Blink every .25 sec

35 int state = 0;

36 snprintf(path, MAXSTR, "%s%s%s%s", GPIOPATH, "/gpio", pin, "/value");

37 fp = fopen(path, "w");

38 while (1) {

39 fseek(fp, 0, SEEK_SET);

40 if (state) {

41 fprintf(fp, "1");

42 } else {

43 fprintf(fp, "0");

44 }

45 state = ~state;

46 usleep(250000); // sleep time in microseconds

47 }

48}

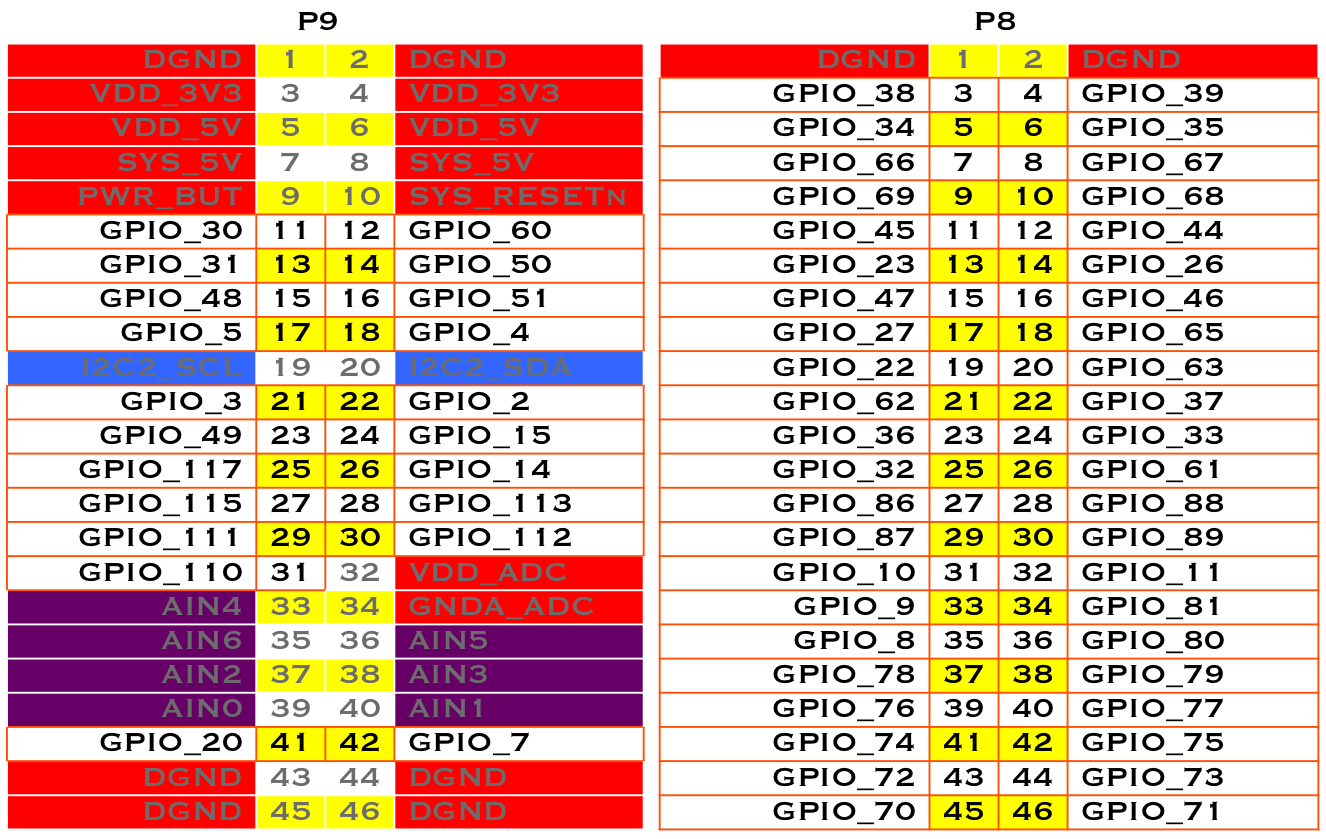

Here, as with JavaScript and Python, the gpio pins are referred to by the Linux gpio number. Mapping from header pin to internal GPIO number shows how the P8 and P9 Headers numbers map to the gpio number. For this example P9_14 is used, which the table shows in gpio 50.

Fig. 335 Mapping from header pin to internal GPIO number¶

Compile and run the code:

bone$ gcc -o blinkLED blinkLED.c

bone$ ./blinkLED

^C

Hit ^C to stop the blinking.